Aging Brains

Understand Aging Brains

As we age our brains shrink in volume, particularly in the frontal cortex. As our vasculature ages and our blood pressure rises the possibility of stroke and ischemia increases and our white matter develops lesions. Memory decline also occurs with aging and brain activation becomes more bilateral for memory tasks.

How the Aging Brain Affects Thinking

The brain controls many aspects of thinking — remembering, planning and organizing, making decisions, and much more. These cognitive abilities affect how well we do everyday tasks and whether we can live independently.

Some changes in thinking are common as people get older. For example, older adults may:

- Be slower to find words and recall names

- Find they have more problems with multitasking

- Experience mild decreases in the ability to pay attention

Aging may also bring positive cognitive changes.

For example, many studies have shown that older adults have more extensive vocabularies and greater knowledge of the depth of meaning of words than younger adults. Older adults may also have learned from a lifetime of accumulated knowledge and experiences. Whether and how older adults apply this accumulated knowledge, and how the brain changes, as a result, is an area of active exploration by researchers.

Despite the changes in cognition that may come with age, older adults can still do many of the things they have enjoyed their whole lives. Research shows that older adults can still:

- Learn new skills

- Form new memories

- Improve vocabulary and language skills

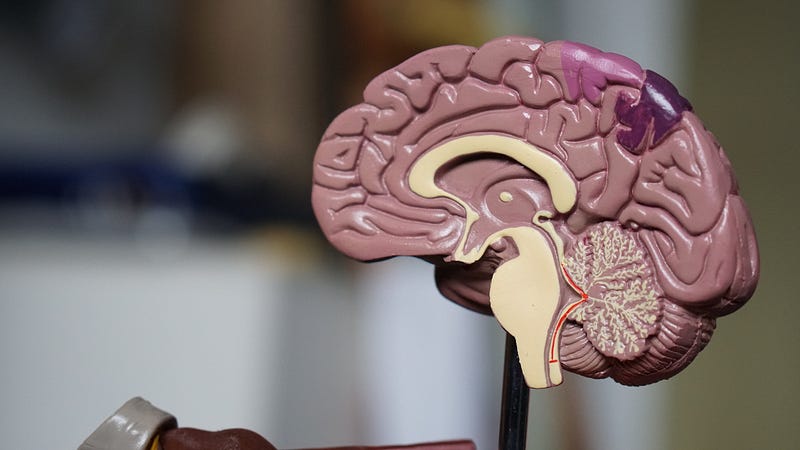

Changes in the Aging Brain

As a person gets older, changes occur in all parts of the body, including the brain.

- Certain parts of the brain shrink, especially those important to learning and other complex mental activities.

- In certain brain regions, communication between neurons (nerve cells) may not be as effective.

- Blood flow in the brain may decrease.

- Inflammation, which occurs when the body responds to an injury or disease, may increase.

These changes in the brain can affect mental function, even in healthy older people. For example, some older adults may find that they don’t do as well as younger individuals on complex memory or learning tests. However, if given enough time to learn a new task, they usually perform just as well.

Needing that extra time is normal as we age. There is growing evidence that the brain maintains the ability to change and adapt so that people can manage new challenges and tasks as they age.

Talk with your doctor if you’re concerned about changes in your thinking and memory. He or she can help you determine whether the changes in your thinking and memory are normal, or whether they could be something else.

There are things you can do to help maintain your physical health and that may benefit your cognitive health, too. Learn more about cognitive health and take steps to help you stay healthy as you age.

Aging and the brain

Aging causes changes in brain size, vasculature, and cognition. The brain shrinks with increasing age and there are changes at all levels from molecules to morphology. Incidence of stroke, white matter lesions, and dementia also rise with age, as does the level of memory impairment and there are changes in levels of neurotransmitters and hormones.

Protective factors that reduce cardiovascular risk, namely regular exercise, a healthy diet, and low to moderate alcohol intake, seem to aid the aging brain as does increased cognitive effort in the form of education or occupational attainment. A healthy life both physical and mental may be the best defense against the changes of an aging brain. Additional measures to prevent cardiovascular disease may also be important.

The effects of aging on the brain and cognition are widespread and have multiple aetiologies. Aging has its effects on molecules, cells, vasculature, gross morphology, and cognition. As we age our brains shrink in volume, particularly in the frontal cortex. As our vasculature ages and our blood pressure rises the possibility of stroke and ischemia increases and our white matter develops lesions.

Memory decline also occurs with aging and brain activation becomes more bilateral for memory tasks. This may be an attempt to compensate and recruit additional networks or because specific areas are no longer easily accessed.

Genetics, neurotransmitters, hormones, and experience all have a part to play in brain aging. But, it is not all negative, higher levels of education or occupational attainment may act as a protective factor. Also protective are a healthy diet, low to moderate alcohol intake, and regular exercise. Biological aging is not tied absolutely to chronological aging and it may be possible to slow biological aging and even reduce the possibility of suffering from age-related diseases such as dementia.

Physical changes

- It has been widely found that the volume of the brain and/or its weight declines with age at a rate of around 5% per decade after age 40 with the actual rate of decline possibly increasing with age, particularly over age 70.

- The shrinking of the grey matter is frequently reported to stem from neuronal cell death but whether this is solely responsible or even the primary finding is not entirely clear.

- It has been suggested that a decline in neuronal volume rather than number contributes to the changes in an aging brain and that it may be related to sex with different areas most affected in men and women.

- Additionally, there may be changes in the dendritic arbor, spines, and synapses. Dendritic sprouting may occur thus maintaining a similar number of synapses and compensating for any cell death.

- Conversely, a decrease in dendritic synapses or loss of synaptic plasticity has also been described. Functional organizational change may occur and compensate in a similar way to that found in patients after recovery from moderate traumatic brain injury.

- Brain changes do not occur to the same extent in all brain regions. That these brain changes are not uniform is supported by a longitudinal study, using two MRI scans separated by around one or two years, and by a review of cross-sectional studies.

- The latter included only those studies that compared younger (aged less than 30) and older (greater than 60) groups to compare wider age ranges and in contrast with much of the other work in this area.

- The finding is that the prefrontal cortex is most affected and the occipital least fits well with the cognitive changes seen in aging, although some studies also suggest that aging has the greatest effect on the hippocampus.

- Men and women may also differ with frontal and temporal lobes most affected in men compared with the hippocampus and parietal lobes in women.

Cognitive change

- The most widely seen cognitive change associated with aging is that of memory. Memory function can be broadly divided into four sections, episodic memory, semantic memory, procedural memory, and working memory.

- The first two of these are most important about aging. Episodic memory is defined as “a form of memory in which information is stored with ‘mental tags’, about where, when and how the information was picked up”.

- Episodic memory performance is thought to decline from middle age onwards. This is particularly true for recall in normal aging and less so for recognition. It is also a characteristic of the memory loss seen in Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

- Semantic memory is defined as “memory for meanings”, for example, knowing that Paris is the capital of France, that 10 millimeters make up a centimeter, or that Mozart composed the Magic Flute.

- Semantic memory increases gradually from middle age to the young elderly but then declines in the very elderly. It is not yet clear why these changes occur and it has been hypothesized that the very elderly have fewer resources to draw on and that their performance may be affected in some tasks by slower reaction times, lower attentional levels, slower processing speeds, detriments in sensory and or perceptual functions, or potentially a lesser ability to use strategies.

- There have been studies investigating different types of memory in aging using neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging. However, it must be pointed out that it is sometimes methodologically difficult to separate some of these functions

- Older brains tend to show more symmetrical activation, either because they have increased activation in a hemisphere that is less activated than in younger adults or because they show reduced activation in the areas most activated in younger adults.

- This has been shown for visual perception and memory tasks. The observed changes in activation in the left and right prefrontal cortex are in keeping with changes in memory performance, particularly episodic memory, as this is thought to be based in this area.

- It has also been suggested that the actual level of brain activation, as shown in neuroimaging, may be related more directly to the levels of memory performance.

- The increased symmetrical hemispheric activation is a robust finding and has been referred to as HAROLD or hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults. It is not clear whether this change is an attenuation of the response seen in younger subjects, an inability to recruit specific areas, or an attempt to compensate for the aging process.

- This change in activation occurring in the frontal lobes fits with changes in memory performance and with the possible white matter changes referred to above, however, other factors such as changes in neurotransmitter or hormone levels also require consideration.

Mechanisms of change

- The neurotransmitters most often discussed in aging are dopamine and serotonin. Dopamine levels decline by around 10% per decade from early adulthood and have been associated with declines in cognitive and motor performance.

- It may be that the dopaminergic pathways between the frontal cortex and the striatum decline with increasing age, or that levels of dopamine itself decline, synapses/receptors are reduced or binding to receptors is reduced.

- Serotonin and brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels also fall with increasing age and may be implicated in the regulation of synaptic plasticity and neurogenesis in the adult brain

- A substance related to neurotransmitter levels, monoamine oxidase, increases with age and may liberate free radicals from reactions that exceed the inherent antioxidant reserves.

- Other factors that have been implicated in the aging brain include calcium dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and the production of reactive oxygen species.

- Another factor to consider about the aging brain and its cognitive performance is hormonal influence. It is known that sex hormones can affect cognitive processes in adulthood and that changes in sex hormones occur in aging particularly in women at menopause.

- Women also have a higher incidence of AD even when longer life expectancy is taken into account.AD is characterized by failing memory and there has been a suggestion that estrogen therapy may increase dopaminergic responsivity and play a protective part in AD.

- It must be remembered though that the use of HRT has recently been shown to have cancer risks. Growth hormone levels also decline with age and may be associated with the cognitive performance although the evidence is far from clear.

- The aging brain may also suffer from impaired glucose metabolism or a reduced input of glucose or oxygen as cerebrovascular efficiency falls, although the reduction in glucose may partly be attributable to atrophy rather than any change in glucose metabolism. Change in the vasculature is important and other common findings in elderly brains related to ischemia are white matter lesions and stroke.

Vascular factors and dementia

- WML, strokes, and dementia increase with increasing age. WML shows levels of heritability, are common in the elderly even when asymptomatic, and are not the benign finding they were once thought to be.

- WML or hyperintensities are related to increased cardiovascular risk and a reduction in cerebral blood flow, cerebral reactivity, and vascular density although it is unclear if the WML prompts the vessel loss or vice versa.

- They may also be associated with further tissue changes in grey matter visible when using magnetization transfer magnetic resonance imaging.

- WML is found more in frontal rather than posterior brain regions in keeping with cognitive and morphological findings discussed above and the fact that WML is related to poor cognition has been shown

- Other damages associated with aging and related to blood pressure and vascular factors include strokes and small vessel disease. Moderate to high 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure has been related to increased brain atrophy as has increased variability of systolic blood pressure.

- In Japanese subjects raised systolic blood pressure was related to grey matter volume loss in a cross-sectional study and in the Framingham offspring cohort, an increased 10-year risk of the first stroke was associated with decrements in cognitive function.

- The authors suggest that this may be attributable to cerebrovascular-related injuries, accelerated atrophy, white matter abnormalities, or asymptomatic infarcts.

- That cerebral vasculature could be related to cognitive function is not surprising because microvasculature’s ability to respond to metabolic demand falls with increasing age and functional adult neurogenesis may be related to good capillary growth.

- Increasing evidence points to vascular factors not only contributing to cognitive problems in aging but also the two most common dementias seen in this population. The prevalence of dementia increases almost exponentially with increasing age with around 20% of those aged 80 affected rising to 40% of those aged 90.

- The dementia types seen most frequently in the elderly are AD accounting for around 40%–70% of dementia, and vascular dementia (VaD) 15%–30%.

- In recent years, it has seemed increasingly likely that there is an overlap between these two dementias and there have been calls for AD to be reclassified as a vascular disorder or for dementia to become a multifactorial disorder A postmortem study found that 77% of VaD cases showed AD pathology and high blood pressure has been associated with increased neurofibrillary tangles characteristic of AD.

- Multiple types of vascular pathology have been associated with AD including microvascular degeneration, disorders of the blood‐brain barrier, WML, microinfarctions, and cerebral hemorrhages.

- It has been suggested that large vessel factors, for example, atherosclerosis, increase the risk of AD and may play a part in cerebral vessel amyloid deposition.AD patients do show significantly higher levels of cerebrovascular pathology when compared with controls at postmortem examination although this did not correlate with the severity of the cognitive decline.

- The characteristic neurofibrillary tangles and plaques found in AD are also evident to some degree in most elderly brains at postmortem examination even those without symptoms, as are white matter lesions.

- The issue of normal aging is a difficult one because there are studies that show cognitively intact adults aged 100, and yet a high percentage suffer from dementia, and the line between mild cognitive impairment and normal memory changes is still a little blurred.

- Risk factors that have been put forward about aging and the development of dementia include hypertension, diabetes, hyperhomocysteinemia, and high cholesterol although the evidence for all but hypertension is far from clear.

Protective factors

- That diet may have a part to play in biological aging and the development of cognitive decline is raised by studies showing that a diet higher in energy and lower in antioxidants is a risk factor alongside studies showing that energy restriction may prolong life, reduce oxidative damage, or ameliorate/protect against cognitive decline.

- Increased consumption of fish and seafood, even only once a month, may be protective and reduce stroke.

- Consumption of antioxidant supplements may be protective although the evidence for other preparations purported to aid cognitive function, such as ginkgo Biloba or piracetam is mixed.

- In addition to a healthy diet, low to moderate alcohol intake may reduce cardiovascular risk and may stimulate the hippocampus. Alcohol seems to show a U or J-shaped curve such that teetotal people or heavy drinkers are disadvantaged whereas moderate drinkers show reduced WML, infarcts, and even dementia.

- Exercise is also beneficial and studies have shown increased executive functioning and even a reduction in the aging expected decline of white and grey tissue density with increased fitness.

- As is shown by the studies mentioned above, biological age is not always synchronized with chronological age, particularly in cardiovascular risk factors.

- The lower cardiovascular risk may be linked to lower biological age and vice versa. Another factor to consider about cognitive decline is the effect of intelligence and environmental factors such as schooling and occupation contributing to a cognitive reserve that protects against decline despite neuropathology although there is not total support for this theory.

Changes That Occur to the Aging Brain: What Happens When We Get Older

It’s no secret that our bodies change as we grow older. Over time, we feel aches and pains in the joints we once used to spring up and out of bed in the morning. But in addition to our bodies changing as they grow older, our brains are also constantly transforming throughout our lives — and it’s not as simple as you might think. Some functions like memory, processing speed, and spatial awareness deteriorate as we age, but other skills like verbal abilities and abstract reasoning improve.

Why does this happen, though? And what does the changing nature of our most complex organ tell us about our aging selves and our aging population from a public health perspective?

What Changes Occur When the Brain Ages?

In the early years of life, the brain forms more than a million new neural connections every second. By the age of 6, the size of the brain increases to about 90% of its volume in adulthood.

Then, in our 30s and 40s, the brain starts to shrink, with the shrinkage rate increasing even more by age 60. Like wrinkles and gray hair that start to appear later in life, the brain’s appearance starts to change, too. And our brain’s physical morphing means that our cognitive abilities will become altered. The following changes normally occur as we get older:

- Brain mass: While brain volume decreases overall with age, the frontal lobe and hippocampus — specific areas of the brain responsible for cognitive functions — shrink more than other areas.

- The frontal lobes are located directly behind the forehead. They are the largest lobes in the human brain and are considered to be the human behavior and emotional control centers for our personalities.

- The hippocampus is a complex brain structure embedded deep into the temporal lobe. It plays a major role in learning and memory. Studies have shown that the hippocampus is susceptible to a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders.

- Cortical density: This refers to the thinning of the outer corrugated surface of the brain due to decreasing synaptic connections. Our cerebral cortex, the wrinkled outer layer of the brain that contains neuronal cell bodies, also thins with age. Cortical thinning follows a pattern similar to volume loss and is particularly pronounced in the frontal lobes and parts of the temporal lobe. Lower density leads to fewer connections, which could contribute to slower cognitive processing.

- White matter: White matter consists of myelinated nerve fibers that are bundled into tracts and transmit nerve signals between brain cells. Researchers believe that myelin shrinks with age, slowing down processing and reducing cognitive function. White matter is a vast, intertwining system of neural connections that join all four lobes of the brain (frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital), and the brain’s emotion center in the limbic system.

- Neurotransmitter systems: The brain begins to produce different levels of chemicals that affect neurotransmitters and protein production, ultimately leading to a decline in cognitive function.

With these changes, older adults might experience memory challenges like difficulty recalling names or words, decreased attention, or a decreased ability to multitask.

As the brain ages, neurons also begin to die, and the cells also produce a compound called amyloid-beta. Amyloid beta is what is typically associated with Alzheimer’s.

It can also be found in the brain of an aging individual. If there are amyloid-beta plaques (prions) in the brain, it can be a sign of Alzheimer’s disease. And when there are signs of plaque, but no prions, it may be a sign of normal aging.

The Truth About Aging and Dementia

As we age, our brains change, but Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are not an inevitable part of aging. Up to 40% of dementia cases may be prevented or delayed. It helps to understand what’s normal and what’s not when it comes to brain health.

Normal brain aging may mean slower processing speeds and more trouble multitasking, but routine memory, skills, and knowledge are stable and may even improve with age. It’s normal to occasionally forget recent events such as where you put your keys or the name of the person you just met.

When It Might Be Dementia

In the United States, 6.2 million people age 65 and older have Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type of dementia. People with dementia have symptoms of cognitive decline that interfere with daily life — including disruptions in language, memory, attention, recognition, problem-solving, and decision-making. Signs to watch for include:

- Not being able to complete tasks without help.

- Trouble naming items or close family members.

- Forgetting the function of items.

- Repeating questions.

- Taking much longer to complete normal tasks.

- Misplacing items often.

- Being unable to retrace steps and getting lost.

7 Ways to Help Maintain Your Brain Health

Studies show that healthy behaviors, which can prevent some kinds of cancer, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease may also reduce your risk for cognitive decline. Although age, genetics, and family history can’t be changed, the Lancet Commission on dementia prevention, intervention, and care suggest that addressing risk factors may prevent or delay up to 40% of dementia cases.

- Quitting smoking now may help maintain brain health and can reduce your risk of heart disease, cancer, lung disease, and other smoking-related illnesses.

- Maintain a healthy blood pressure level. Tens of millions of American adults have high blood pressure, and many do not have it under control. Learn the facts.

- Be physically active. CDC studies show physical activity can improve thinking, reduce the risk of depression and anxiety and help you sleep better.

- Maintain a healthy weight. Healthy weight isn’t about short-term dietary changes. Instead, it’s about a lifestyle that includes healthy eating and regular physical activity.

- Get enough sleep. A third of American adults report that they usually get less sleep than the recommended amount.

- Stay engaged. There are many ways for older adults to get involved in their community.

- Manage blood sugar. Learn how to manage your blood sugar especially if you have diabetes.

Conclusion

- That the brain changes with increasing chronological age is clear, however, less clear is the rate of change, the biological age of the brain, and the processes involved.

- The brain changes that may affect cognition and behavior occur at the levels of molecular aging, intercellular and intracellular aging, tissue aging, and organ change.

- There are many areas of research under investigation to elucidate the mechanisms of aging and to try to alleviate age-associated disorders, particularly dementias that have the biggest impact on the population. In terms of personal brain aging, the studies suggest that a healthy lifestyle that reduces cardiovascular risk will also benefit the brain.

- Medical care in this area may even offer limited protection in terms of cognitive decline but this needs to be shown for antihypertensives, antiplatelet, and anticholesterol agents.

- It is also important to take note of the limitations in studies on the aging brain. Many studies are cross-sectional, have small numbers of participants with wide ranges in chronological age, lack control for risk factors or protective factors, take no account of education that may improve performance on cognitive tests, and finally lack assessment about depression that may also affect performance.

- It must be remembered that the brains of an elderly group may show cohort effects related to wider environmental influences, for example, lack of high-energy foods while growing up.

- Future studies need to take full account of these factors and “cross sequential”, a combination of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies has been proposed.

- It is clear that our understanding of the aging brain continues to grow but still requires much research which is especially important given the number of elderly people in society and their potential levels of cognitive impairment.

- Where appropriate, randomized controlled trials of therapeutic measures may, in the future, lead the way to greater understanding.

Comments

Post a Comment